Google ADK - Sessions, state, and memory

Imagine you built a travel-booking agent. A user says, “Find flights to Paris, and the agent returns options. Then the user says, “Book the second one.” Without any memory of the previous turn, the agent has no idea what “the second one” refers to. The conversation is dead. This is the fundamental problem with LLMs. LLMs are stateless. Every API call to an LLM is independent. The model does not inherently remember what was said before. Yet meaningful conversations are inherently multi-turn, contextual, and stateful. This is where agent memory comes into play. Agent memory is the system built around the LLM to allow it to retain information, learn from past interactions, and maintain continuity within and across conversations.

Agent memory

At a high-level, there are three types of memory.

- Short-term or working memory is what’s currently visible within the model’s context window. This is needed for continuity in the current conversation. It includes the current prompt, the immediate conversation history, and a scratch pad where the agent reasons through a problem. This memory is volatile. The information in this memory will be lost once the conversation ends or the context limit is reached. There are methods to compact the context and continue the conversation.

- Long-term memory is usually stored externally, mostly in a vector database, and retrieved when needed using techniques such as RAG. This is used to store events & experiences (episodic memory) and facts & knowledge (semantic memory). This allows an agent to recall user preferences, past decisions, and specific interaction history.

- Procedural memory is the implicit knowledge of how to perform tasks. This is usually represented by the available tools and instructions for using them.

When developing agents with Google ADK, sessions and memory enable the agent to retain information, learn from past interactions, and maintain continuity within and across conversations. Let us dive into these concepts.

Sessions

A session in Google ADK is a single, ongoing interaction between the user and your agent. Think of it as one chat thread. It contains the chronological history of everything that happened (as Events) and a scratchpad of data relevant to this conversation (State). A Session object is the container for one conversation thread. Some of the key properties of the Session object are:

| Property | Type | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

id |

str |

Unique identifier for this specific conversation |

app_name |

str |

Which agent application does this belong to |

user_id |

str |

Which user owns this conversation |

state |

dict |

Key-value scratchpad |

events |

list[Event] |

Chronological history of all interactions |

last_update_time |

float |

Timestamp of the most recent event |

To create and manage sessions, we use the SessionService.

|

|

You can list all sessions for a user using the list_sessions method.

|

|

To get an existing session, we use the get_session method.

|

|

We can use the delete_session method to delete a session.

|

|

InMemorySessionService stores all session data directly in the application’s memory; therefore, all conversation history will be lost if the application restarts. The DatabaseSessionService and VertextAiSessionService provide session persistence. The InMemorySessionService service is a good fit for quick development and local testing.

As discussed, a Session object is a container for a conversation thread. This object contains state and events.

State

The state is the agent’s working memory for the current conversation, and it is a dictionary holding key-value pairs. This is the agent’s scratchpad, which is updated during a conversation. This scratchpad can be used to track and recall information such as user preferences and task execution progress, and to store any information that will be useful during an agent’s execution. For the state, the keys must be strings. The values associated with these must be serializable.

You can organize session state into multiple scopes. This is determined using the prefix on the state keys. Scope determines who can see the state and how long it lives.

Session Scope

When the state key has no prefix, it becomes a part of the current session scope. This is useful for tracking progress on the current task or for temporary flags.

session.state['current_step'] = 'payment' sets the current_step key to payment in the current session.

User Scope

When the state keys has user: prefix, it becomes a user state. It gets tied to user_id and is shared across all sessions for that user within the same application (app_name). This scoped state is best for storing user preferences and task-specific details for the user.

session.state['user:preferred_payment_mode'] = 'card' sets and tracks user’s payment mode preference.

App Scope

You can use the app scope when you need state that is shared across all users and sessions for an application. This is useful for global settings that apply to all users and all sessions.

session.state['app:payment_api'] = 'http://payments.yourbank.com' sets app-wide the payments API endpoint.

Temporary Scope

Finally, if you want to track the state within the current invocation only, use the temp prefix. For example, state variables such as tool call results, which are relevant only to the current invocation, can be set as a temp scope.

session.state['temp:raw_api_response'] = {...} sets raw_api_response as a state variable in the current invocation.

Except for the temporary scoped state, other scoped states can be persisted when using the database or Vertex AI services as a session service.

Your agent code sees a single, flat session.state dictionary. The SessionService handles the magic of merging state from different scopes behind the scenes. When you read session.state['user:name'], the service fetches it from the user-level store. When you read session.state['cart_total'], it comes from the session-level store. It’s all transparent.

Events

Everything that happens in a session is recorded as an event. Events are the fundamental units of information flow in Google ADK agents. They carry user messages, agent responses, tool calls, tool results, state changes, and control signals. An event loop is at the heart of the ADK runtime and facilitates the communication between the Runner component and the agent execution. When a user prompt arrives, the Runner hands it over to the agent for processing. The agent runs until it has something to yield, at which point it emits an event. The Runner receives the event, processes any associated actions, calls the session service to append the event to the current state, and forwards the event. After the Runner completes event processing, the agent resumes from where it was paused and continues this loop until it has no more events to yield. The Runner component is the central orchestrator of this event loop. The agent or execution logic running within the event loop yields or emits events. An event has the following structure.

We will dive into

Runnerand its architecture in a later part of this series.

| Field | Purpose |

|---|---|

id |

Unique identifier for this specific event |

invocation_id |

Groups all events from one user-request-to-final-response cycle |

author |

'user' or agent name (e.g., 'WeatherAgent') |

content |

The payload (text, function calls, or function responses) |

actions |

Side effects (state_delta, artifact_delta, transfer_to_agent, escalate) |

timestamp |

When this event was created |

partial |

True if this is a streaming chunk, not yet complete |

Besides the content, the actions field contains an important piece of information that decides the next step in the event loop. The actions field is where state changes and control flow signals live. State is never updated in-place. Every state change flows through an Event’s state_delta. When the SessionService processes append_event(session, event), it reads event.actions.state_delta and applies those changes to the persisted state. This is the only reliable path for state updates.

In an earlier article on building a multi-agent workflow using Google ADK, we saw how event.actions.escalate was used to signal the workflow’s termination.

Reading and writing state

You can read state from a Session object, from CallbackContext, or from ToolContext:

|

|

There are three ways to write to the session state.

output_keyis the simplest, for saving the agent’s final text response.EventActions.state_deltais used for manual and complex updates.CallbackContext.state/ToolContext.stateis recommended for callbacks and tools.

We should never modify the session.state directly on a session object retrieved by the SessionService. This bypasses event tracking, breaks persistence, and is not thread-safe.

output_key

We have seen in earlier articles in this series that using output_key stores the agent’s response in the session state. This is the simplest method and is useful when we need to capture the agent’s complete response so that other agents and tools can refer to it.

|

|

After the agent runs the session.state['last_greeting'] will contain something like "Hello there! How can I help you today?". This method only captures text, cannot store structured data, multiple keys, or scoped keys like user:.

EventActions.state_delta

We can use the state_delta event action for fine-grained control over what gets stored and when. Using this method, we can manually construct the state changes, wrap them in an Event, and append it.

|

|

This method is useful for system-level updates, multi-key updates, updates to scoped state keys, and other scenarios not tied to the agent’s direct text response.

CallbackContext and ToolContext

For modifying state inside callbacks and tool functions, using CallbackContext and ToolContext is the recommended approach.

Inside a callback function, you can use the CallbackContext.state to retrieve or update the state. We will learn about callbacks in a future article in this series.

In a tool function, you can use ToolContext.state to retrieve or update the state.

|

|

In both CallbackContext and ToolContext, you write clean, natural code, context.state["key"] = value, and the framework handles creating EventActions, populating state_delta, calling append_event, and ensuring persistence. There is no boilerplate code required.

Injecting state into agent instructions

One of ADK’s most powerful features: you can embed state values directly into agent instructions using {key} template syntax.

|

|

If session.state contains:

|

|

The LLM receives:

|

|

For this template syntax to work, the key must exist in the state, or the agent will throw an error. We can use {key?} for keys that may be absent. Keys suffixed with a question mark resolve to an empty string if they are missing. The values should be strings or easily convertible to strings. If you need literal curly braces in the agent instructions, you must use InstructionProvider function as shown below.

|

|

This method is useful when we need full control over instruction generation, including bypassing the {key} templating. For example, when your instruction contains literal curly braces for JSON examples, or you need completely dynamic instruction generation based on state.

|

|

If you need to inject state via {key} templating but need to preserve the literal braces, you must use inject_session_state() method.

|

|

The instructions_utils.inject_session_state(template, context) injects the {user:name} state variable but preserves the literal braces.

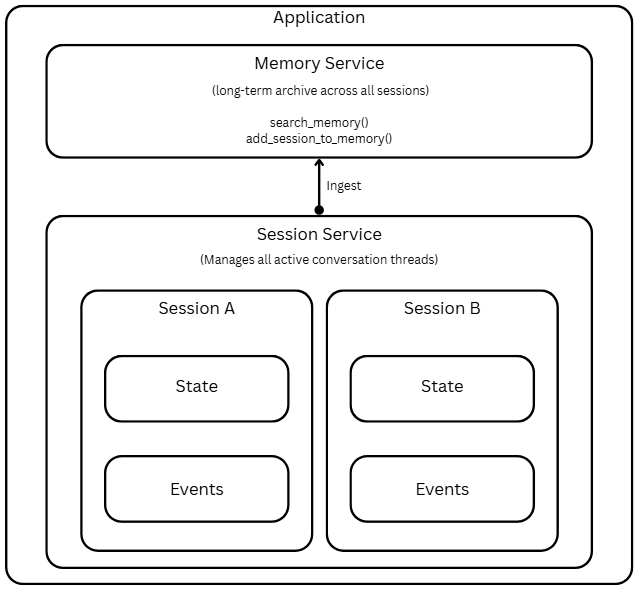

Memory

A session tracks the history and temporary data for a single, ongoing conversation. To enable history and state persistence across conversations and enable agents to recall the information from past interactions, we must use the memory service. There are two types of memory service.

- The

InMemoryMemoryServiceis used for quick prototyping and local testing of agents, and it is good for basic keyword search. Using this requires no setup, stores session data in application memory, and does not provide persistence. - The

VertexAiMemoryBankServiceconnects to the Vertex AI memory bank service and provides LLM-based extraction of meaningful information from sessions. This service persists data in Google Cloud and is production-ready.

Each of these memory services offers two operations.

- Ingest:

memory_service.add_session_to_memory(session)takes a completed session and adds its information to the long-term store - Search:

memory_service.search_memory(app_name, user_id, query)returns relevant snippets from past sessions

These memory services also offer tools that agents can use in their work.

PreloadMemoryToolautomatically retrieves relevant memories at the start of every turn (like a callback that always fires)LoadMemoryTool(orload_memory) lets the agent decide when to search memory (on-demand)

Here is an example of working with InMemoryMemoryService.

|

|

When you run this, the first runner stores the user preference in memory. This is done using add_session_to_memory method. The second runner then uses the basic keyword match provided by the memory service to generate the response. The load_memory tool provided to the recall_agent automatically retrieves the memory for search.

|

|

The process of saving memory can be automated using agent callbacks. We will learn about this in a later article in the series.

Here is another example where we use InMemoryMemoryService and help agent track the conversation progress through state.

|

|

When you run this, you can observe how the agent uses the state updates to track progress.

|

|

Understanding how ADK uses Sessions, state, and memory to enable agents to persist conversational state and recall past interactions is important for developing efficient agent workflows. This article explored this in-depth and demonstrated session and memory capabilities using InMemorySessionService and InMemoryMemoryService. The fundamentals you learned about the overall workflow stay the same for other session and memory service types that provide persistence. I recommend that you experiment with those services.

Comments

Comments Require Consent

The comment system (Giscus) uses GitHub and may set authentication cookies. Enable comments to join the discussion.