Documentation stack for AI agents

We are in the middle of a fundamental shift in how software gets built. LLMs are no longer used as passive autocomplete machines. AI agents reason, plan, retrieve information, and act. An agent is only as good as the knowledge it can access. An LLM’s training data is frozen in time. The Kubernetes API changed last week. Your company shipped a new SDK version this morning. The compliance rules were updated yesterday. If an agent can’t reach this knowledge at inference time, it hallucinates, generates deprecated code, or simply gives up.

The solution? Build documentation that agents can consume. Not as an afterthought, but as a deliberate, first-class engineering practice.

In today’s article, we will look at the landscape of agent-consumable documentation. This includes the standards, patterns, and tools that are emerging to bridge the gap between human-written knowledge and machine-readable context.

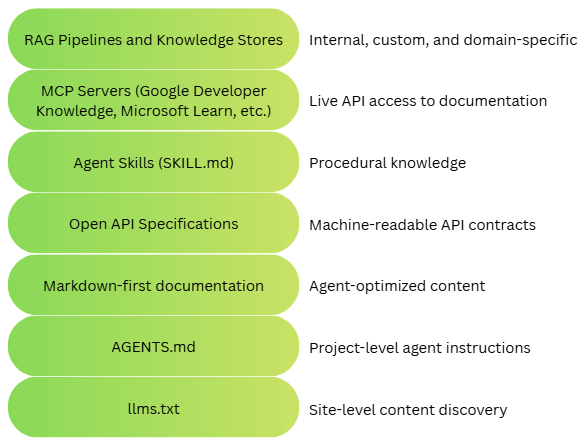

The Documentation Stack

There are various existing and evolving methods to provide knowledge to agents. I like to visualize these options in a stack, the documentation stack.

The layers of this stack represent different ways to provide knowledge to the agents. To understand these options, we will explore a sample use case where a developer needs to implement a feature in an existing project.

The task

A backend developer at a mid-sized e-commerce company has been asked to add Stripe payment processing to the company’s checkout flow. This company uses Google Cloud Run for deployment, follows strict PCI compliance policies documented in an internal wiki, and has a TypeScript/Node.js monorepo with specific architectural conventions.

The developer opens the IDE and asks the AI coding agent:

Add Stripe payment processing to our checkout service. Use Payment Intents and support credit cards and Apple Pay. Deploy to our staging Cloud Run environment when done.

This is a realistic, multi-layered task. The agent needs to:

- Discover what documentation exists for Stripe and Google Cloud.

- Understand the company’s project conventions before writing any code.

- Read the actual Stripe and Cloud Run documentation efficiently.

- Understand the Stripe API contract precisely enough to generate correct API calls.

- Query live documentation services for the latest API details.

- Follow a multi-step deployment procedure.

- Check the company’s internal compliance requirements.

Each of these needs maps to a different layer of the documentation stack shown earlier. Let’s walk through them.

llms.txt

Imagine walking into a massive library for the first time. You don’t start pulling books off random shelves. You go to the information desk and ask: “I need to add payment processing. Where should I start?” The librarian hands you a curated reading list.

That’s llms.txt. It is the librarian’s reading list for an AI agent. If robots.txt tells search engine crawlers what not to index, and sitemap.xml tells them what to index, then llms.txt tells AI agents what to read. It is a plain-text, Markdown-formatted file placed at a website’s root (e.g., https://docs.stripe.com/llms.txt) that provides a curated overview of a site’s most important content. The agent knows it needs Stripe documentation, so it fetches https://docs.stripe.com/llms.txt:

|

|

In seconds, the agent curates a map of exactly where to find information about payment Intents and Apple Pay. It didn’t have to crawl the entire Stripe docs site, parse HTML navigation menus, or guess which pages are relevant.

A valid llms.txt file contains a single H1 heading (the project name), a blockquote summary, and H2 sections with curated link lists. Each link uses the format - [Title](URL): Description. The file lives at the site root and requires zero infrastructure. Stripe, Anthropic, Cloudflare, and dozens of other companies now host llms.txt files. The standard is community-driven and growing as companies recognize AI-discoverability as a competitive advantage.

AGENTS.md

When a new developer joins a team, they don’t just start writing code. They go through onboarding — learn the build system, understand the architecture decisions, and absorb the team’s style preferences. AGENTS.md is the onboarding document for your AI teammate. AGENTS.md is a project-level Markdown file. It is now a part of the Linux Foundation’s Agentic AI Foundation (AAIF). This gives AI coding agents specific instructions for working within a repository. It captures the tribal knowledge that would normally be passed down in Slack threads and code reviews.

Before writing a single line of code, the agent reads AGENTS.md at the root of the company’s monorepo:

|

|

Now the agent knows that the Stripe client should go in src/clients/stripe.ts, the payment logic should go in src/services/payment/, environment variables should go through env.ts, and amounts should be integers in cents. Without this, the agent might have placed files in the wrong directories, used process.env.STRIPE_SECRET_KEY directly, or represented amounts as floating-point numbers, all valid code, but every line violates the team’s conventions.

For large monorepos, AGENTS.md files can be nested. A monorepo might look like:

|

|

The closest AGENTS.md in the directory tree takes precedence. This is similar to how .gitignore scoping works. As of early 2026, AGENTS.md has been adopted by over 60,000 open-source projects and is supported by virtually every major AI coding agent.

Markdown-First Documentation

HTML documentation is like reading a technical manual with full-color illustrations, glossy covers, and marketing inserts. Markdown documentation is the same content typed up in plain text. Both carry identical information, but the email is much easier for a machine to process and much cheaper to process. Several companies now serve their documentation in plain Markdown format, alongside the traditional HTML rendering. Stripe pioneered this: append .md to any Stripe docs URL to get a clean, token-efficient Markdown version of the page.

Using the URLs discovered via llms.txt, the agent fetches the Payment Intents guide in Markdown:

- Human URL:

https://docs.stripe.com/payments/payment-intents - Agent URL:

https://docs.stripe.com/payments/payment-intents.md

The HTML version includes a navigation sidebar, a header bar, a search widget, breadcrumbs, syntax-highlighted code blocks with framework tabs, and a footer with legal links. Rendered to text, it’s thousands of tokens of noise around the actual content.

The Markdown version? Pure signal:

|

|

The agent gets the same knowledge at a fraction of the token cost, in a format it can parse natively. Markdown strips away the signal-to-noise ratio with HTML, delivering pure content. This pattern works with any docs-as-code pipeline. If you build documentation with Hugo, Docusaurus, or MkDocs, the Markdown source files already exist. You just need to make them accessible via HTTP. Documentation platforms like Mintlify, ReadMe, and GitBook are also beginning to offer Markdown endpoints.

OpenAPI Specifications

If llms.txt is the library index and Markdown docs are the books, then an OpenAPI spec is the operating manual for a specific machine. It doesn’t explain philosophy. It tells you exactly which buttons to press, in what order, and what will happen when you do. The OpenAPI Specification (OAS) defines every endpoint, parameter, request body, response format, authentication method, and error code in a structured, machine-readable YAML or JSON document. Where Markdown docs explain concepts, OpenAPI specs define contracts.

With this, the agent reads the conceptual docs and understands Payment Intents. Now it needs to write actual API calls. It fetches Stripe’s OpenAPI spec and finds the precise contract for creating a Payment Intent:

|

|

With this spec, the agent generates type-safe TypeScript code with confidence. It knows the amount is an integer (not a float — consistent with what AGENTS.md also specified), currency is a string, and payment_method_types is an array. No more guessing. Modern agent frameworks (LangChain, Google Agent Development Kit, etc.) can automatically convert OpenAPI specs into callable tools. The agent doesn’t just read the spec — it uses it to act.

MCP Servers

Static files (llms.txt, AGENTS.md) are like textbooks. You read them once and reference them. MCP servers are like having a reference librarian on speed dial. You describe what you need in natural language, and they hand you the exact page. Always current, always relevant to your specific question. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open standard, and it is now part of the Linux Foundation’s Agentic AI Foundation. MCP provides a standardized interface for LLMs to query external data sources and tools. MCP servers expose three primitives: Resources (data to read), Tools (functions to call), and Prompts (templated interactions). MCP creates a uniform interface to heterogeneous knowledge sources. The agent queries Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Stripe docs using the exact same protocol. No more bespoke integrations per vendor. As more documentation providers expose MCP servers, the agent’s reach expands without any code changes.

For the task at hand, the agent has the core Stripe integration working. Now it needs to deploy to Google Cloud Run. Rather than relying on possibly stale training data, it queries the Google Developer Knowledge MCP server directly:

|

|

The agent then fetches the full content of the most relevant documents:

|

|

The agent now has the exact, current Cloud Run deployment syntax and not what was in its training data from months ago, but what’s live in Google’s docs right now. It does the same with the Microsoft Learn MCP server when it needs to verify Azure-specific patterns.

Agent Skills Files

If documentation is a medical textbook that describes what diseases exist, their symptoms, and their mechanisms, then a skill file is a surgical checklist (step 1: verify patient identity; step 2: confirm procedure site; step 3: administer anesthesia). One provides understanding; the other provides an executable procedure. Agent skills files are portable packages of instructions, stored as SKILL.md files, that encode procedural knowledge: step-by-step workflows, not just reference information. Unlike documentation that describes what something is, skills describe how to do something.

For the task the developer prompted, the agent has written the Stripe integration code and knows how to deploy it to Cloud Run. But the company has a specific, multi-step deployment process, including staging validation, smoke tests, and rollback procedures, that isn’t documented externally. This is internal operational knowledge. The monorepo has a skills directory. At startup, the agent loaded only lightweight metadata:

|

|

During stage 1 (Discovery), the agent sees that deploy-to-staging matches the developer’s request. It activates the skill. It is hardly 20 tokens.

In the second stage, activation, the agent reads the full SKILL.md:

|

|

In the final stage, as needed, the agent checks scripts/pci-check.sh to understand what the compliance check does and opens scripts/smoke-test.sh to see which endpoints it validates. This layered loading is critical. If the agent loaded the full contents of all 15 skills at startup, it would consume thousands of tokens of irrelevant context, degrading its performance on the actual task. Progressive disclosure works like how humans process information. You scan chapter titles (Layer 1), open the relevant chapter (Layer 2), and check the appendix only if you need a deep dive (Layer 3). The agent does the same. Skills are used by Claude Code, Gemini CLI, Kiro, and various agent frameworks. The open-standard structure (Markdown + optional scripts/resources) makes them portable.

RAG Pipelines

If MCP is a reference librarian, RAG is an entire research department. You don’t just get directed to the right book. A team of researchers reads through thousands of internal documents, extracts the relevant passages, and synthesizes a briefing tailored to your exact question. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) ingests documents, converts them into vector embeddings, stores them in a vector database, and retrieves relevant chunks at query time to augment the agent’s context. It’s the catch-all for knowledge that doesn’t fit into static files or public APIs.

For the task at hand, the agent has written the code, run tests, and loaded the deployment skill. But before deploying, the agent remembers that AGENTS.md mentioned PCI compliance and that the skill’s prerequisites include running a PCI check. The agent needs to understand the company’s specific PCI requirements.

This knowledge lives in an internal Confluence wiki. Not on a public website, not in the repo, and not available through any MCP server. But the company’s platform team has set up a RAG pipeline over their internal documentation.

The agent queries the RAG system:

|

|

This is gold. The agent now adds a sanitize() call to its logging middleware, implements idempotency keys for payment creation (something it might not have done otherwise), and double-confirms that it’s using integer cents, with the organizational context for why.

The most powerful pattern is Agentic RAG, where the agent dynamically decides when and from which sources to retrieve. The agent in our example demonstrated this naturally. It consulted llms.txt, AGENTS.md, Markdown docs, an OpenAPI spec, MCP servers, a skill file, and the RAG pipeline, orchestrating across all seven layers within a single task.

As you see in this scenario, no single layer was sufficient. Each contributed a different type of knowledge. However, you may not always need all seven layers. So, how do you choose?

Here’s a decision framework:

| Your Need | Start With | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Help external AI agents discover your site | llms.txt |

Zero infrastructure, widely supported |

| Guide coding agents in your repo | AGENTS.md |

Project-scoped, version-controlled |

| Serve docs content to agents via HTTP | Markdown endpoints (.md) | Token-efficient, no protocol needed |

| Enable agents to call your API correctly | OpenAPI spec |

Precise, machine-actionable |

| Provide a live, queryable docs interface | MCP Server | Standardized, searchable, always current |

| Encode multi-step internal workflows | Skills (SKILL.md) |

Procedural, portable, progressive disclosure |

| Make internal knowledge agent-accessible | RAG pipeline | Flexible, private, any content type |

What’s clear is that the era of documentation-as-an-afterthought is ending. In the age of agents, your documentation is not just a reference for human developers. It is the knowledge infrastructure that powers autonomous systems.

Comments

Comments Require Consent

The comment system (Giscus) uses GitHub and may set authentication cookies. Enable comments to join the discussion.